Why microleaks happen in tinplate double seams during retort and storage, and how to prevent them

When tinplate double-seam sealing failure shows up as microleaks and early spoilage in high-moisture foods, the frustrating part is that the cans often look “fine” on the outside. The reliable way forward is to connect seam geometry, sealing compound behavior, and retort stress to what you can actually measure on your line, then lock those measurements into a repeatable control window.

For packaging and quality teams running high-moisture, often salty or acidic products through hot-fill or retort, the goal is not to “talk about hermeticity” in general terms. The goal is to prevent leakage by controlling the handful of seam variables that open leak paths under thermal cycling, rapid cooling, and long shelf storage.

The good news is that tinplate’s double-seam + sealing compound system is fundamentally a strong engineering solution: a mechanically interlocked barrier that can tolerate handling loads and thermal processing when overlap, tightness, and compound distribution stay within limits. The bad news is that a small drift in those limits can look like a minor dimensional issue but behave like a shelf-life risk.

What “tinplate double-seam sealing failure” looks like in high-moisture foods

In high-moisture food production, seal integrity loss rarely announces itself with a dramatic leak at the seamer. More often it appears as subtle microleakage that only shows up after processing and distribution: sporadic swollen cans, flat sour outcomes, or inconsistent yields that trace back to a small subset of seamer heads, an end lot change, or a compound distribution shift.

When the seam is not truly hermetic, the impact is disproportionate. A small leak path can allow microbial ingress, compromise sterility margins, and trigger complaints or recalls. Even without immediate spoilage, seam damage that exposes steel under lacquer can accelerate corrosion at the seam area, turning a “dimensional drift” into a leakage mechanism over time.

Because the seam is a mechanically formed structure, failures typically cluster into a few recognizable modes: false seam or loose seam; seam wrinkles or droop; incomplete overlap; compound skips or voids; damage from handling; flange or end curl defects; and lacquer damage that becomes corrosion-driven leakage later. Each of these modes is tied to a control point you can specify and verify.

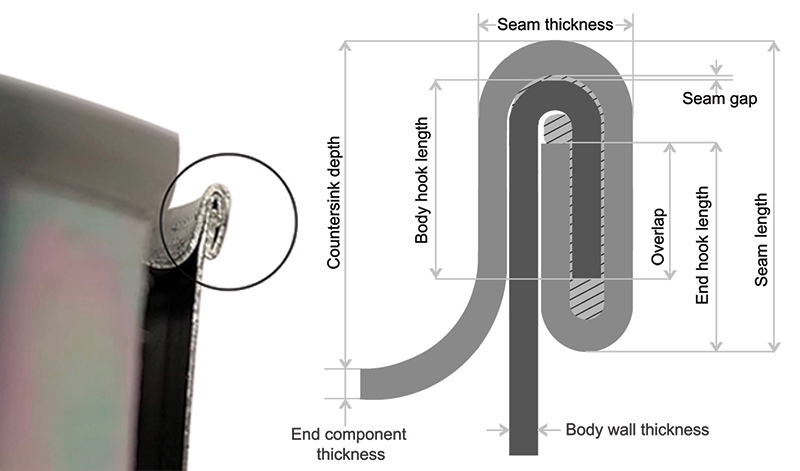

It helps to treat the seam as a system with two “gates.” The first gate is the formed geometry: the hooks must interlock with enough overlap and tightness to resist separation during thermal cycling. The second gate is sealing compound continuity: even a good-looking seam can leak if compound coverage has voids or if it is displaced under process stress.

Why high-moisture + retort conditions amplify seam risk

High-moisture products tend to be processed and stored in ways that are unforgiving to seam variation. Thermal processing and cooling change metal dimensions and stress the compound; storage humidity and product chemistry can raise corrosion potential at any exposed seam steel; and distribution shocks can damage a seam that is already operating near the edge of its process window.

Retort profiles create a repeating expansion–compression environment. If overlap is short or the seam is loose, that cycling can open microscopic gaps that are invisible in casual external inspection. If compound distribution is marginal, heating can soften and shift it, while cooling can contract the seam and leave discontinuities where the compound no longer fills the intended leak path.

High-moisture foods often include salt or acidity, which can make seam corrosion more likely if lacquer integrity is compromised. That is why lacquer coating damage is not just a “cosmetic” concern. It is a pathway to long-duration seam weakening, and later leakage, especially when storage humidity supports corrosion growth.

Root causes: the controllable variables behind microleaks

Most microleaks do not come from one dramatic defect; they come from a combination of small deviations. For practical control, focus on the causes that map directly to measurements and process adjustments: seam geometry, end and flange condition, compound distribution, handling damage, and retort-induced stress on the seam system.

1) Seam geometry drift: overlap and tightness fall out of the safe window

Overlap is the core mechanical “insurance policy.” Too-short overlap is strongly associated with leakage because the interlock does not resist separation when thermal and mechanical loads are applied. Tightness matters because a seam that is too loose can keep internal spaces that become leak paths, while a seam that is too tight can damage coatings or distort components in ways that create their own failure modes.

Geometry drift often happens gradually: tooling wear, setup changes, head-to-head variability, or subtle changes in can body material thickness and end properties. In practice, it shows up as measurement trends rather than a single out-of-spec event, which is why routine cross-section inspection is a cornerstone of control.

2) End curl and body flange conditions: defects that the seamer cannot “fix”

Even a well-maintained seamer cannot compensate for a damaged flange or an end curl defect that prevents proper hook formation. Handling and feeding issues can nick or bend the flange; end curl variation can cause inconsistent hook formation; and these issues can lead to incomplete overlap, wrinkles, or false seams that may only be detected after teardown.

When quality teams see microleaks clustered around a specific can or end lot, it is often more productive to verify flange and end condition early than to chase seamer settings alone. The seam is an interlock: if one component geometry is compromised, the finished seam may look acceptable but behave poorly under stress.

3) Sealing compound skips and voids: the hidden leak path

The sealing compound is the seam’s conformal barrier. When compound application is inconsistent, or when distribution shifts during seaming, voids can remain. In a high-moisture pack, those voids can become the path that defeats otherwise acceptable seam geometry.

Compound issues are especially important when your process includes retort and rapid cooling. Compound material can soften during heating and be displaced by pressure and deformation. If the compound was already marginal, the post-process seam may fail a vacuum/pressure leak test even when teardown measurements appear close to target.

4) Seam damage after seaming: handling and line interactions

Microleaks can be created after a seam is formed. Impacts during conveying, can-on-can contact, or poor transfer points can dent or scuff seam areas. This kind of damage often produces intermittent failures that are hard to reproduce in short runs but appear in distribution or after storage.

For high-moisture products, post-seam damage is particularly costly because the product and process conditions are already “stress tests” for the seam. A seam operating with reduced margin due to geometry or compound variation can cross the failure threshold after one more small insult on the line.

5) Lacquer coating damage and seam corrosion: a delayed failure mode

Lacquer integrity matters because it protects tinplate from corrosion, especially near the seam where crevice-like conditions can exist. If the coating is damaged during seaming or handling, and the product chemistry and storage humidity support corrosion, the seam may lose integrity over time.

This is where high-moisture, salty, or acidic products deserve extra caution. A can that passes immediate leak checks can still drift into leakage risk after weeks or months if corrosion progresses at the seam area. That is why a retort simulation followed by leak verification is a more realistic proof point than a single immediate test.

How to diagnose the cause without turning the line into a lab

For packaging engineers and QA teams, the most efficient diagnosis approach is staged: confirm whether the issue is head-specific or lot-specific, then use teardown and leak checks to decide whether the primary mechanism is geometry, compound, handling damage, or delayed corrosion risk.

Start by asking a practical question: are failures clustered by seamer head, by time, or by material lot? A head-specific cluster points toward settings, tooling wear, or mechanical issues. A lot-specific cluster points toward end curl, flange condition, coating/compound variability, or body material variation. A time-based pattern can indicate thermal processing changes, cooling changes, or handling interactions.

Next, align observations with measurements. Visual seam inspection can catch obvious external deviations such as droops and vees, but microleaks often require internal cross-section measurement and a leak test to confirm whether the seam’s interlock and seal path are stable.

Finally, treat retort and cooling as part of the diagnostic loop. If seams pass before retort but fail after, that strongly suggests a thermal-stress interaction: marginal overlap, compound displacement, coating damage, or stress-induced opening of micro-gaps. If seams fail sporadically regardless of retort, handling damage or intermittent material defects move higher on the list.

Practical prevention: build a seam “control window” instead of chasing single numbers

Microleaks are rarely eliminated by a single adjustment. They are eliminated by keeping several variables inside a defined process window that remains stable across production time, seamer heads, and material lots. That is the buyer-friendly framing: specify what matters, ask suppliers for evidence, and lock line controls around measurable limits.

At the center of the control window is seam geometry stability. Routine seam teardown and dimensional measurement should confirm overlap and tightness signals remain consistent across heads. The objective is not to hit a single target once; it is to prevent drift that creates low-margin seams on the edges of normal variation.

Compound control belongs in the same window. Instead of treating compound application as “the lid supplier’s job,” treat it as a verified input: compound weight and distribution consistency should be supported by supplier evidence and by your own incoming checks when risk is high.

Handling control is the third leg. If seam damage occurs after seaming, the solution often lives in transfer points, can guides, and spacing rather than in the seamer itself. The prevention mindset is to protect the seam’s margin: a seam built with good overlap and compound still loses value if it is dented or scuffed in the seam area.

Because this support page focuses on one failure topic, it does not attempt to cover every tinplate procurement variable. When you need the broader buyer evaluation logic for tinplate packaging in high-moisture production, place this seam control window inside the full framework found in How Buyers Evaluate Tinplate Packaging for High-Moisture Food Production, then use the evidence requests and acceptance checks to reduce supplier and scale-up risk.

Verification and standards: how to prove the seam is controlled, not just “good-looking”

Hermeticity is only actionable when it is verified with methods that reflect the stresses of your process. For tinplate cans used in hot-fill or retort high-moisture foods, a standards-anchored verification plan typically combines seam teardown & dimensional measurement, visual seam inspection, leak tests, and retort simulation followed by leak verification. The purpose is to confirm that overlap, tightness, and compound behavior remain stable after processing.

Seam teardown and dimensional measurement of overlap, tightness indicators, and related geometry is the primary “mechanism check.” It answers whether the seam has the mechanical interlock needed to stay closed under thermal cycling. Visual seam inspection complements this by catching external deviations early, which is useful for monitoring head-to-head variability during production.

Leak testing—vacuum/pressure leak testing or dye penetration leak checks—adds “outcome verification.” It does not replace geometry checks; it validates whether the formed seam actually blocks leak paths. For high-moisture, retorted products, retort simulation followed by leak verification is often more meaningful than a pre-retort check alone because it tests the seam after the same stress that will occur in production.

For teams that want a clear view of how standardized methods are managed and referenced globally, it can help to review the official home pages of ISO y ASTM International as starting points for locating applicable testing and measurement methods. The key constraint is not the organization name; it is using test types that match your seam failure mode, your retort stress, and your storage environment.

Microbiological assurance is the final confidence layer. Incubation or microbiological challenge approaches are not seam geometry tools; they are hermeticity assurance checks that help validate that the total system—seam formation plus process profile—delivers the shelf-life outcomes you need. When microleaks are suspected, these outcome-oriented checks can help confirm whether seam improvements actually reduce spoilage risk, rather than only improving a measurement on paper.

Supplier evidence and acceptance checks that reduce scale-up surprises

Because this topic sits at the intersection of supplier capability and your own line control, the best buyer strategy is to request evidence that maps directly to the failure pathways: seam teardown datasets that demonstrate stable overlap and geometry; compound weight and distribution control data; and proof that seams remain leak-tight after retort simulation, not only immediately after seaming.

In high-moisture, salty/acidic environments with long storage, add coating integrity as a risk control. A buyer does not need a marketing story about lacquer; they need confirmation that the coating is not being damaged in the seam zone during forming, and that the system resists seam corrosion pathways that can lead to delayed leakage.

Acceptance checks should be staged to match the production reality. Incoming material checks help prevent lot-driven variability. In-process checks catch head-to-head drift before it becomes product loss. Finished-pack checks after retort and cooling confirm that the seam’s mechanical interlock and compound continuity survive the same stress you will apply in production.

A low-pressure next step that makes seam risk easier to manage

If you are specifying tinplate cans for high-moisture products with hot-fill or retort, a quick way to reduce leakage risk is to align three items up front: what seam teardown dimensions you will accept, how compound distribution is controlled, and which leak verification steps will be used after retort simulation. When that evidence is clear, comparing options becomes a straightforward control-window discussion instead of a trial-and-error exercise.

Source and methods note

This content is developed around the practical relationship between tinplate double-seam mechanics, sealing compound continuity, and the stress profile created by hot-fill or retort processing, rapid cooling, and long-duration storage in high-moisture, often salty/acidic conditions. The verification approach described relies on widely used test types such as seam teardown & dimensional measurement, visual seam inspection, vacuum/pressure leak testing, dye penetration checks, and retort simulation followed by leak verification, with outcome confirmation supported by incubation or microbiological hermeticity assurance methods where appropriate.